local-first apps: The Service Worker

Welcome to part 2 of my, hopefully, multiple-part series on Local-First Applications. Last time, we talked about CouchDB and PouchDB which are the data layer for making your app truly local, letting your users manage their data even if they're offline. PouchDB holds it locally and syncs it to CouchDB, when online. You can find that article here: CouchDB and PouchDB for Local Data.

To build a proper local-first app, you need not just the data offline, but the entire application must load, function, and feel snappy even on the slowest connections or, worst case, no connection at all. That is why today, we discuss the Service Worker.

What is a Service Worker?

A Service Worker is nothing more than a simple JavaScript file that your browser runs in the background, separate from your main web page. Think of it as a programmable network proxy that sits between your page and the internet. Once it is installed and activated, every network request your app makes goes through the Service Worker first.

This unique position allows it to intercept requests, answer them from cache, decide what to do with them, and fundamentally change how your app interacts with the user.

Using Workbox

The main thing you want to do with a Service Worker in order to achieve an offline experience is caching. The Service Worker uses the Cache API to store resources locally. When a request comes in, the Service Worker can check its local cache first, and serve the resource from there instead of going to the network.

Writing all this logic by hand, managing versions of assets, and ensuring a smooth update process can become, how shall I say, pretty unwieldy pretty fast. This is where Workbox comes in.

Workbox is a set of JavaScript libraries from Google that makes dealing with Service Workers much, much easier. It provides high-level modules to handle routing, precaching (caching essential files during installation), and runtime caching (caching assets as they are requested). It is almost always a good idea to use Workbox in order to get reliable offline caching.

You can find more information about the modules on the Workbox Documentation.

Service Worker + PouchDB

The combination of Service Workers and PouchDB is the magic ingredient for a truly local-first experience.

As we covered, PouchDB handles your data by storing it in IndexedDB locally and then synchronizing it with a remote CouchDB instance when a connection is available.

The Service Worker, however, is responsible for the application's assets. It ensures that the PouchDB library itself, your application's JavaScript bundles, your CSS files. Using WorkBox, you should always use the network-first for your main index.html file, and cache-first for versioned assets, like JS files and CSS files.

The Service Worker makes sure that when the user opens your app, they can immediately access the cached PouchDB code, which in turn gives them access to their locally stored data. This way, the user can start working immediately, regardless of their network status. So even if they are offline they can work.

Once the user gets online and has the app open, the data gets synced to the central CouchDB instance.

The Manifest

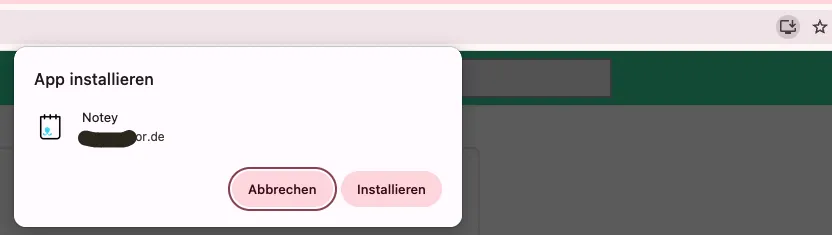

The final piece of the local-first puzzle that goes hand-in-hand with Service Workers is the Web App Manifest. A Service Worker makes your app work offline, but the Manifest makes it installable and look like a native app.

The Manifest is a simple JSON file that tells the browser how your app should appear when installed on a user's device or computer.

This is where you define details like:

nameandshort_name: What appears on the homescreen.icons: The pretty pictures for different resolutions.start_url: Which page loads when the user opens the app (usually/index.htmlor/).display: For example,standalonewhich makes the app launch without the browser's typical address bar and navigation elements, letting it feel much more like a regular application.

In order to be a proper Progressive Web App (PWA), you absolutely must have a Service Worker and a Web App Manifest. The Manifest lets the browser, if supported, present the install prompt to the user, and the Service Worker makes the app actually functional once it is installed and launched.

Generating Assets and Manifests

Creating all the necessary icons and splash screens for different device resolutions is a tedious and error-prone process. Why not automate it?

Tools like @vite-pwa/assets-generator can automate the creation of all your PWA assets, including app icons, splash screens, and favicons. You just provide a single source image, often an SVG, and the tool generates all the necessary sizes and even helps you update your manifest.json and HTML files accordingly.

It needs a simple configuration file. For example:

import {

defineConfig,

minimal2023Preset as preset,

} from "@vite-pwa/assets-generator/config";

export default defineConfig({

headLinkOptions: {

preset: "2023",

},

preset,

images: ["public/pwalogo.svg"],

});

This way, your app is ready to be installed with minimal work. Highly, highly recommended.

Conclusion

The Service Worker is the essential brick in the wall of a true local-first application. It is the gatekeeper of the network, ensuring that your application's logic and assets are always available to the user. When combined with a local-first data store like PouchDB, you get a highly resilient and fast user experience.

I recommend this stack especially for what I like to call user-shardable applications, i.e. where its not possible or extremely seldom for users to try to share data between themselves. Basically, writing a social network local-first might be a challenge, where as good use cases are personal fitness apps or note taking apps.